Homelessness Australia is not a provider of accommodation. If you are seeking emergency accommodation, click here for more information.

Homelessness Australia is not a provider of accommodation. If you are seeking emergency accommodation, click here for more information.

May 30, 2022

by Sandra Harben, Cultural Consultant and Research Coordinator, Noongar Mia Mia

This article was originally published in Parity magazine. Learn more about Parity magazine including how to access full editions.

Noongar Mia Mia (NMM) is the largest Aboriginal-owned-and-operated Community Housing Provider exclusively serving Aboriginal tenants and their families on Noongar country. NMM believes that housing is a human right, and is keen to make a difference by reducing Aboriginal homelessness. Dedicated to the socio-economic inclusion of the Aboriginal community living on Noongar country, we give voice to the voiceless and advocate for selfdetermination and cultural security in the housing sector. In our recent work on the Noongar Housing First Principles and Noongar Cultural Framework, we have created an evidence-based body of knowledge designed to embed greater cultural effectiveness among housing and support providers working with both Noongar and Aboriginal people on Noongar country.

There have been some groundbreaking, very promising changes in the mainstream housing sector, in the form of Housing First — an international model which does not expect people to be ‘housing-ready’. Unlike the conventional approach of treating housing as a reward for the ‘deserving poor’, Housing First acknowledges that people have the right to a home; to choice and self-determination; to be supported and treated with dignity.

However, the Housing First Principles for Australia are missing a cultural perspective in their approach to ‘housing and supporting people who are experiencing long-term and reoccurring homelessness and who face a range of complex challenges’, leading to Leah Watkins (co-author of the Principles) calling for further research into a culturally-effective approach for Australia’s Aboriginal people.

As a result, Shelter WA engaged NMM to develop a Housing First Principles Model using a cultural lens, based on the cultural context of the Noongar people. As the Noongar Cultural Consultant responsible for this project, I have engaged in cultural research and extensive stakeholder consultation, with an outcome of two distinct, complementary resources.

Firstly, a Noongar Cultural Framework (NCF) providing vital background understanding of Noongar cultural values, enabling service providers to work with Aboriginal people living on Noongar country in a culturally-effective way; to be equipped to truly listen, and to work with respect and from the heart. The second resource is the Noongar Housing First Principles (NHFP), a set of Principles building on the mainstream Housing First Principles for Australia but reimagining these through a Noongar cultural context, so that our rights are respected and we are not under pressure to continue to deny our cultural rights and values within the housing systems. These give us the right to practice our culture, to be who we are.

Together, these resources will assist housing providers and support services — from the boardroom to the frontline — to create culturally safe environments and housing and support services for Noongar and Aboriginal people in Noongar boodjar (land). The on-the-ground expertise of an Aboriginal organisation supporting Noongar and Aboriginal people is powerful, and my work has been as a conduit, bridging a robust cultural framework with what that could and should look like on the ground in a housing context, bringing together the wisdom of Elders with the day-to-day realities of Aboriginal caseworkers yarning with ‘our people’. I encourage readers to watch this space as Noongar Mia Mia releases professional development for the housing and support sector organisations based on my findings, which will cover the Framework and Principles in depth and introduce how this knowledge can be put into practice.

This article introduces the Noongar Cultural Framework; the Noongar Housing First Principles will be introduced in a separate article.

The Noongar Cultural Framework has been developed to promote the cultural competency of the housing sector and to support the implementation of Noongar Housing First Principles in the southwest of Western Australia. Noongar Mia Mia is confident the framework truly reflects a process which encompasses the cultural knowledge, understanding and experiences that are associated with a commitment to Noongar ways of thinking, working, and reflecting, incorporating specific and implicit cultural values, beliefs and priorities from which Noongar standards are derived, validated and practiced. Going along together, we can lay the foundation for reducing Aboriginal homelessness, improve Aboriginal health and ensure the well-being of all Noongar and Aboriginal people boordawan — future.

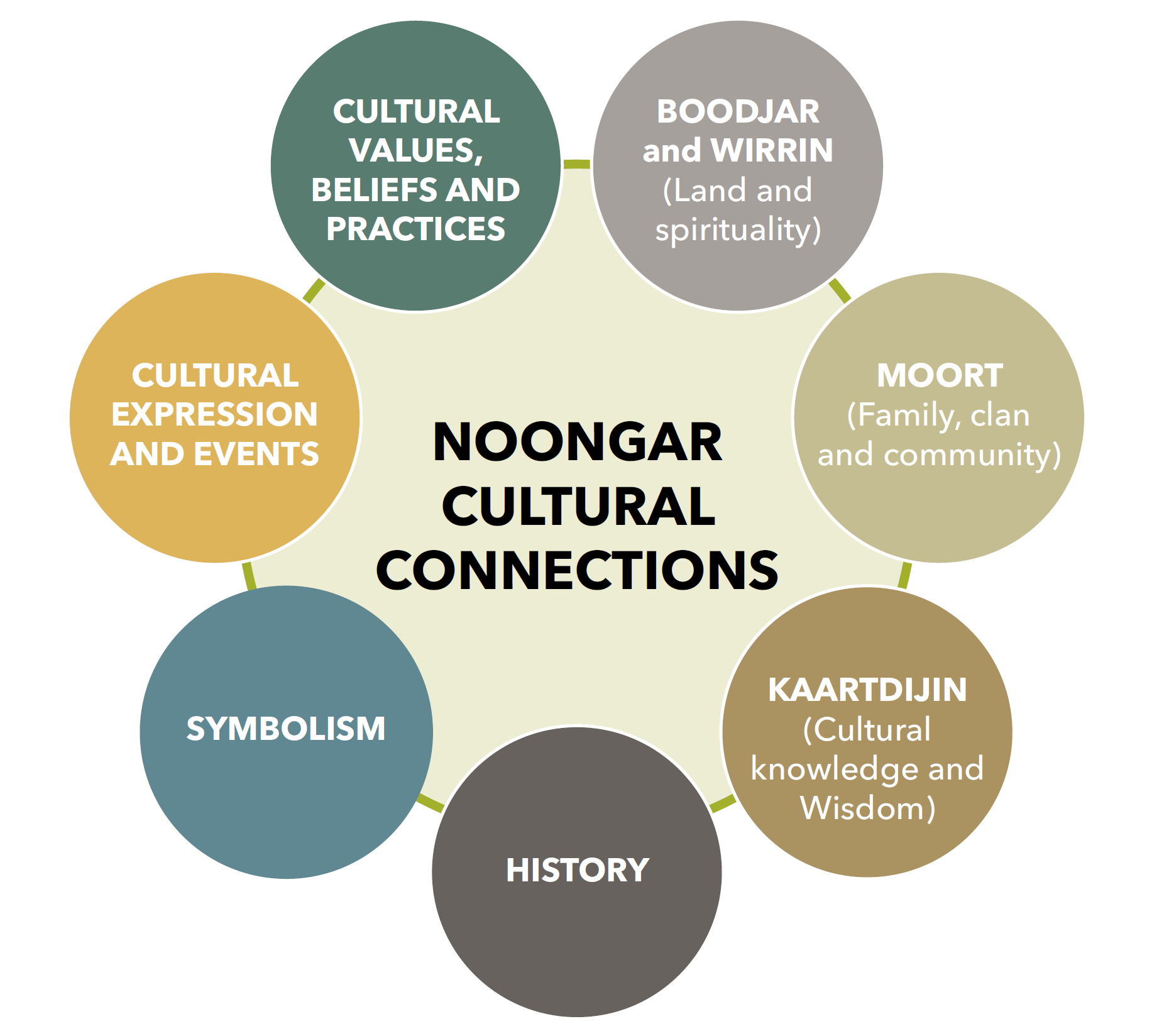

For Noongar people, culture is the foundation upon which everything else is built, underpinning all aspects of life including connections to boodjar (land, country), moort (family, kin and community) and kaartdijin (cultural knowledge and wisdom) through the expression of traditional and contemporary forms of cultural expression. These cultural values and connections are shown within the following diagram:

This diagram has been used as a basis in this Framework to explore and identify key cultural values linked to Noongar lore.

Lore has been practiced by Noongar people since the beginning of time, determines the cultural values of

the Noongar nation, and connects the people to boodjar, moort and kaartdijin (land, family and cultural knowledge). Like all Aboriginal cultures, Noongar people place great importance on the survival and protection of culture, languages and identity, and pass down cultural knowledge down through stories (Dreaming), art, song and dance. Noongar lore is linked to kinship and mutual obligation, sharing and reciprocity. Therefore, all Noongar people are connected to a home and to others (through the Noongar kinship system) and have the right to access kaartdijin (cultural knowledge).

Noongar people have lived in the Southwest of Western Australia since time immemorial. There is archaeological evidence that confirms that the Noongar people have lived on the boodjar since the Nyittiny (the beginning of time). Some caves at Devil’s Lair in the hills near Margaret River showing human habitation from 47,000 years ago. The Noongar people share an ancient body of lore/law and customs prescribing rights and obligations regarding all aspects of landscape. Strong spiritual beliefs govern Noongar worldviews, mythical creatures, stories and obligations are associated with many geographical features of the landscape.

Noongar people have a deep connection with their boodjar which is central to their spiritual identity. This connection remains despite many Noongar people no longer living on their land. Noongar people describe the land as sustaining and comforting, and intrinsic to health, relationships, culture and identity. The Noongar people’s cultural connection to boodjar connects everything across the vast landscape with meaning and purpose. Connection to country is the Noongar people’s spiritual and physical care for the environment and for their places of significance. It is a belief that everything is connected: past and present, people, land and sea, plants and animals; boodjar is holistic and all-encompassing.

A Noongar person’s boodjar links them to their moort (family) and bidis (paths). Noongar people may feel deeply connected to certain boodjar because it’s where their roots are, where their family has historically lived. To leave it involuntarily would be a form of spiritual homelessness.

Noongar spirituality lies in the belief of a cultural landscape and connection between the human and spiritual realms. Spirituality is expressed through many avenues such as paintings, storytelling, music and dance. These avenues offer a way of connecting through nature, paying respect to ancestral creators, and showing the close relationship the Noongar people have with the spiritual beings of the land. The Noongar people’s spiritual connection relates to beliefs and customs surrounding creation, life, death and spirits

of the earth, guiding the way of understanding, navigating and how to use the land, and also influencing cultural practices.

Noongar people are connected to their boodjar through their moort. Noongar stories (kaartdijin — cultural knowledge) about their boodjar are passed down from generation to generation. Connection to boodjar, moort and kaartdijin symbolise strengthening of Noongar lore, keeping people and their wirrin strong, creating healthy families and ensuring cultural continuity.

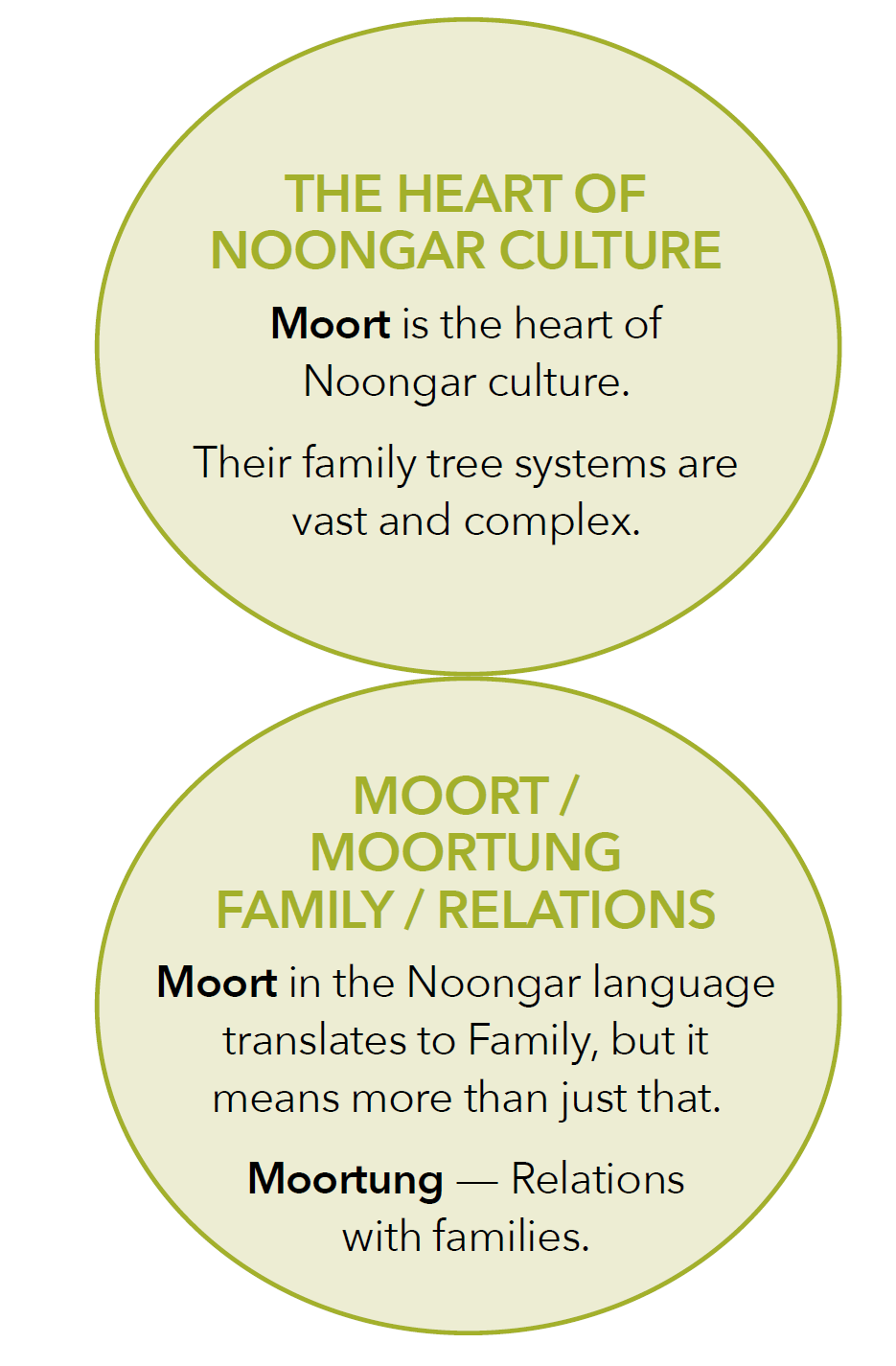

Noongar people acknowledge families are the greatest supports for each other. Knowing your family, and where you come from, is an essential part of identity.

Parents play a vital role in letting children know who they are in relation to family, kin, people, environment and the living spirits of their ancestors and land. These relationships help define a child’s identity, defining how they are connected to everything in life.

Noongar families differ from Western ‘nuclear’ families, tending to be large and close-knit. A Noongar person might have more than one mother and father, and more siblings than just biological siblings. They may refer to non-biological brothers and sisters as ‘cousin-brother’ and ‘cousin-sister’. Key aspects of moort relationships include koorndarn respect) for kin, obligations and reciprocity.

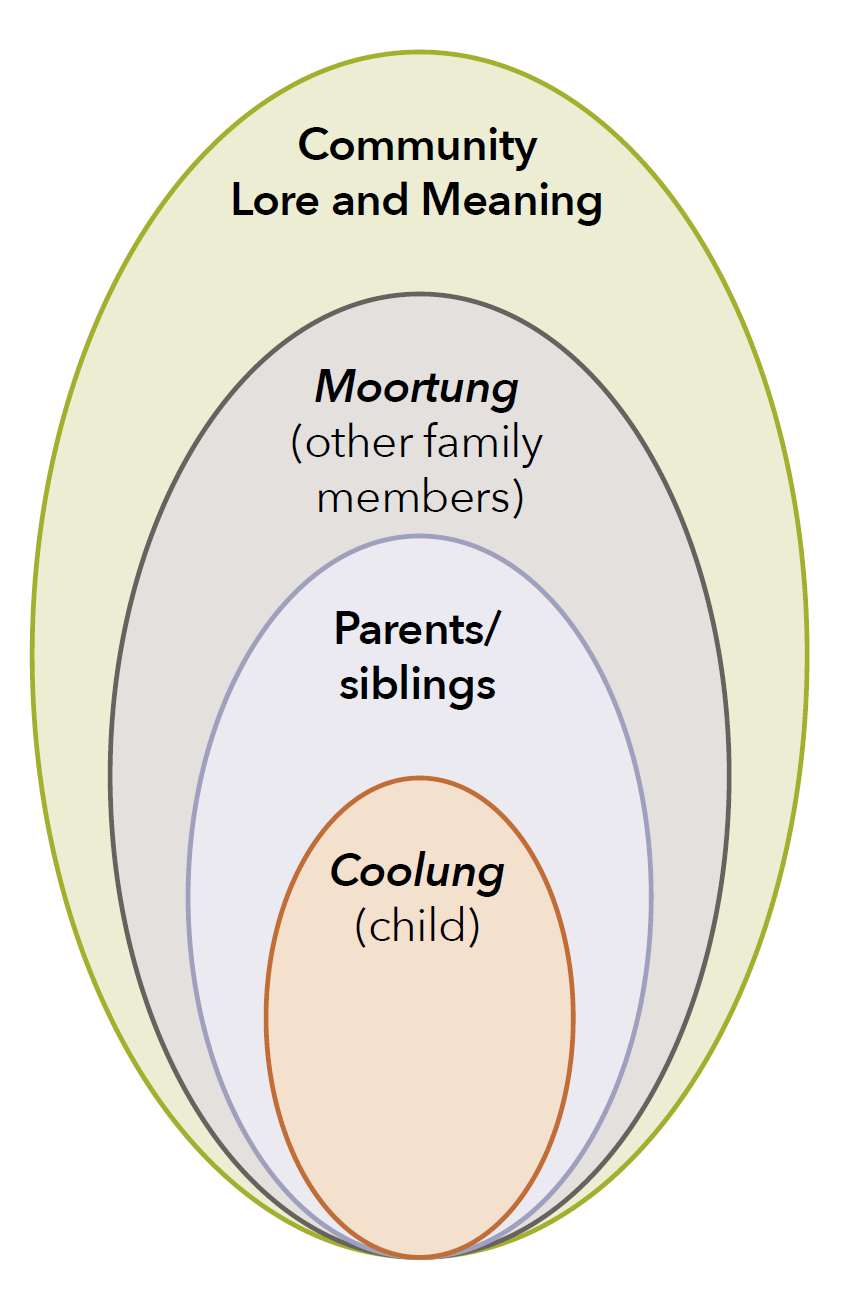

The diagram below shows a typical Noongar family structure. Noongar kids understand the people who are important in their life, who will support them, whom they can rely on: their family.

Aboriginal cultural knowledge can be defined as: “… accumulated knowledge which encompasses spiritual relationships, relationships with the natural environment and the sustainable use of natural resources, and relationships between people, which are reflected in language, narratives, social organisation, values, beliefs, and cultural laws and customs.”

Kaartdijin connects people to boodjar, moort and everything in the landscape. As per oral tradition, Noongar people begin to understand the importance and significance of their ancestor’s country through stories they are told, particularly by their moort. They learn about the significance of sites, and their associated stories. From a very early age, they understand the lore of the land, everything it embodies, and the importance of preserving relationships to land.

Elders play vital leadership roles in Noongar communities. They are identified and respected people who have the trust, knowledge and understanding of their culture and permission to speak about it. Elders often provide a vital source of wisdom, advice and support for Noongar people (particularly youth) in a confidential way. They pass on cultural knowledge across many generations, which is put into practice through Lore.

Unwritten knowledge, beliefs, rules and customs are passed from generation to generation and are central to Noongar identity and practice. Cultural identity is important for people’s sense of self and how they relate to others. A strong cultural identity can contribute to overall wellbeing. Noongar people maintain their cultural identity through boodjar, moort and kaartdijin.

Respect means valuing and honouring another person — both their words and actions — even if we do not

approve of, understand, or share everything he or she does. Accepting the other person, as a person, rather

than trying to change them. Respect is key to developing trust and relationships. Noongar people use the word koorndarn to ensure people practice cultural norms of respect. A Noongar person might respond to a situation where they feel disrespected by saying ‘You need to have some koorndarn’ or telling someone off ‘you have got no koorndarn’, ‘where is your koorndarn’ (in other words, ‘where is your respect’).

Koorndarn (respect) is a very important component of personal identity and interpersonal relationships. Being respected is a basic human right. Respect means not judging people negatively by their attitudes, behaviours or thoughts, or expecting them to be someone they are not.

Noongar people’s interaction with service providers has been filled with false promises without follow-through; consultation for consultation’s sake, which seems to lead nowhere; opinions solicited and then ignored. This has led understandably to mistrust of mainstream people and systems. Engaging in kwop daa (good talk) means speaking openly and honestly; listening to people; involving them; being honest and reliable; not making promises you can’t keep.

Feeling shame, shyness, humiliation or embarrassment. Service providers must take care not to embarrass

a person by making them feel kaarnya, or do or say something that makes them feel like they have no wirrin (spirit), causing them to feel ashamed, shy, humiliated or embarrassed. Service providers should take a stance that nothing is too hard —no blame, and no shame! — and focus on building relationships of respect, rapport, trust, and collaboration. Indigenous people report experiences of vulnerability, humiliation and shame in dealings with public housing around issues such as rent arrears, and previous debts and difficulties in managing their housing.

Love, kindness, compassion, protecting others, caring, sharing, kindness and concern, motherly love, obligations to one other.

Wellbeing Research by Shelter WA 4 proposes a three-part ecology in which (beyond the connection to water and electricity supply commonly accepted as necessary to contemporary Australian dwellings and communities) three connections are deemed non-negotiable when considering Indigenous dwellings or communities:

In Parity 2016, Kake highlights that ‘research shows that disconnection from one’s place of origin and culture leads to fragmentation of identity, whereas access to one’s culture and a sense of belonging (both physically and spiritually) creates a secure identity.’ Like many Indigenous peoples, our identity is not only personal — it is deeply cultural and collective, imbued with place-based meanings.

By respecting the intrinsic, nonnegotiable nature of Noongar cultural values including boodjar, moort and kaartdijin to Noongar (and broadly, Aboriginal) wellbeing, and placing these key cultural building blocks at

the centre of anything designed to serve Aboriginal peoples, the housing and support sectors can provide

more culturally-effective services.

Having accepted that cultural effectiveness must be central, the next question is ‘how?’, and the Noongar Housing First Principles show what this can look like.

This article was originally published in Parity magazine. Learn more about Parity magazine including how to access full editions.

This week is National Reconciliation Week 2022, with the theme Be Brave. Make Change – a challenge to all Australians to be brave in tackling the business of reconciliation so that we can make change for the benefit of all Australians. Learn more about National Reconciliation Week.

Join our mailing list to stay up to date.

"*" indicates required fields